It’s early September 1993, and 17-year-old Christopher Simmons is determined to kill someone.

The Missouri teenager makes plans with his friends to sneak into a trailer park, tie up a 46-year-old woman, duct tape her mouth and eyes, and throw her over a nearby bridge into the water below. And at 2 a.m. on Sept. 9 with two companions, he does exactly that.

Simmons doesn’t try to hide the crime. In fact, he brags to his friends about killing Shirley Ann Crook. After he’s arrested, he confesses to the police without much prompting.

While this might seem like just another murder, Simmons’ crime would turn into a landmark case establishing the difference between a crime committed by a juvenile and one committed by an adult. What’s more, the case, known as Roper v. Simmons, would become one of the earliest instances in which the U.S. Supreme Court cited neuroscience in its decision.

Roper v. Simmons and Neuroscience

The use of neuroscience in the law is by no means new. We’ve had electroencephalography (EEG) and lie detection tests for decades. But Francis Shen, an associate law professor at the University of Minnesota and the executive director of education for the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Law and Neuroscience, says the law is using neuroscience as evidence and during sentencing more often. And experts are applying what they’ve learned to try and reshape the way juveniles are treated in the legal system.

Take Simmons’ murder of Crook, for example. The central question the Supreme Court debated in Roper v. Simmons is whether it’s cruel and unusual to have a juvenile sentenced to death. It wasn’t the first time the court considered this. In 1989, the justices concluded in the case of Stanford v. Kentucky that it’s within a state’s rights to determine whether it’s appropriate to execute someone under the age of 18.

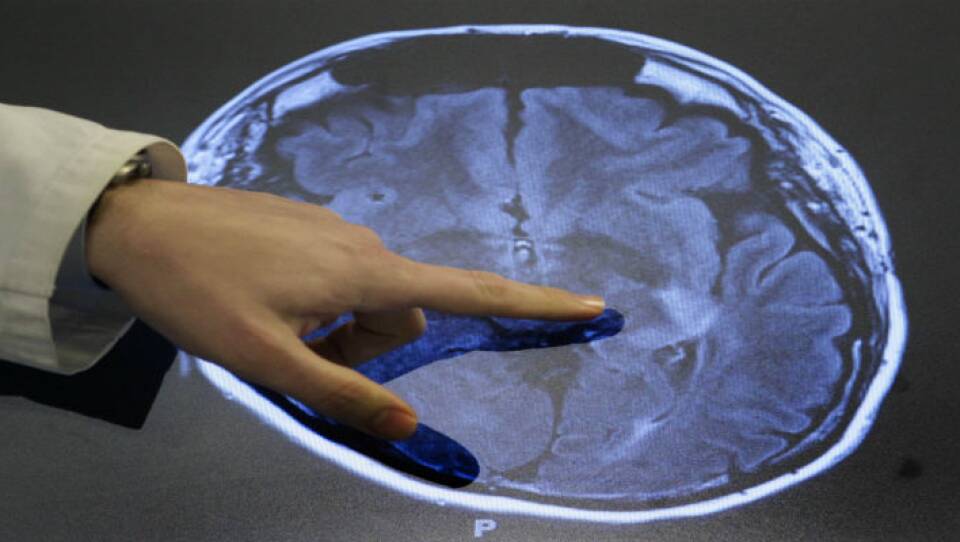

But with Roper v. Simmons, the 2005 court had neuroscience research at its disposal. The American Psychological Association filed an amicus brief with evidence showing that the adolescent brain isn’t fully formed. One part reads:

"Emerging from the neuropsychological research is a striking view of the brain and its gradual maturation, in far greater detail than seen before. Although the precise underlying mechanisms continue to be explored, what is certain is that, in late adolescence, important aspects of brain maturation remain incomplete, particularly those involving the brain’s executive functions."

And according to Frances Jensen, author of “The Teenage Brain: A Neuroscientist's Survival Guide to Raising Adolescents and Young Adults,” this development is what makes juveniles so unpredictable.

“We do see teenagers have greater challenges controlling their impulses, controlling their emotional ability,” Jensen said in a 2016 interview on Innovation Hub, “and [they’re] very susceptible to peer pressure, which is giving an emotional cue to them without that frontal lobe, to say ‘I shouldn’t jump off that cliff, I probably shouldn’t do that.'”

In Roper v. Simmons, the Supreme Court voted 5-4 to bar capital punishment for anyone under the age of 18. Their reasoning? The opinion cited three differences between adults who have reached their 18th birthday and juveniles. Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote:

"First, juveniles lack maturity and responsibility and are more reckless than adults. Second, juveniles are more vulnerable to outside influences because they have less control over their surroundings. And third, a juveniles’ character is not as fully formed as that of an adult.”

With the justices’ nod toward the APA’s amicus brief, Nature Magazine points out that many scientists and juveniles consider the result a triumph for neuroscience in the court.

The decision removed 72 people from death row in 12 states. Since then, the Supreme Court has determined that mandatory life sentences without the possibility of parole for juveniles offenders are unconstitutional, based on the same line of reasoning they used in Roper v. Simmons.

The Developing Mind of Young Adults

While the court’s decision in Roper v. Simmons drew a clear line between how the criminal justice system treats juveniles and how it treats adults, it left one group stuck in the middle: young adults. In fact, many believe we need to reconsider how to classify a juvenile based on brain development.

Take, for instance, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, one of the Boston Marathon bombers. Tsarnaev was 19 years old when he helped plant homemade bombs that killed three people and injured hundreds. At age 19, he was considered an adult by the law and was eligible for the death penalty sentence he received. But medical experts, like Laurence Steinberg, stood with the arguments by the defense: Tsarnaev, like many other people his age, had a brain that was still developing and it played a role in his actions. Steinberg wrote in a 2015 Boston Globe opinion piece:

"We can’t point to a specific chronological age at which the adolescent brain becomes an adult brain, because different brain regions mature along different timetables, but important developments, some of which are relevant to sentencing decisions, are still ongoing during the early 20s."

And on the whole, Shen says the law rarely acknowledges this continuous development. Instead, it divides everyone into two rigid groups.

“Right now, you’ve got two options: you put them with the adults, or with the kids. Neither seems too good,” Shen says. “So we really have to reconceptualize the system and that’s really what neuroscience is all about.”

Shen points to San Francisco’s Young Adult Court as a step in the right direction. It’s the first of its kind, partnering with the Superior Court of California, public defenders, the district attorney and other governmental organizations. It bases its mission off of research that finds that the prefrontal cortex of the brain doesn’t fully develop until the early to mid-20s, catering specifically to young adults ages 18 to 25.

And it might be onto something. Young adult courts are popping up around the country — and the world. The New York Times reports that there are young adult courts in Idaho, Nebraska, and New York. And The Centre for Justice Innovation is testing out the concept with five sites in England and Wales.