Recent FBI investigations relevant to the 2016 presidential election have become the latest battleground in our deeply divided and partisan politics.

Some Republicans, disappointed by the lack of charges over Hillary Clinton's emails and distressed by the continuing probe of Russian interference in the 2016 election, suddenly perceive corruption in the FBI. Democrats counter that the casting of doubt on the nation's top national law enforcement agency is an unprecedented outrage.

Everyone agrees that the FBI should be as professional and impartial as possible, and that its investigations should not be driven by any political agenda or vendetta. That has always been the ideal.

But various parties to the current imbroglio have been suggesting that somehow this is the first time the bureau may have fallen short of that ideal — or even been accused of doing so, rightly or wrongly.

Surely there is a massive case of collective amnesia afflicting Washington and much of the media commentariat on that score.

The fact is, controversy about the FBI is anything but new — and achieving political goals of one kind or another have been part of the reason for the FBI since its inception.

Still, the "this is not normal" narrative is strong, and it is also coming from within the FBI community itself.

Chris Swecker, who finished his 24-year bureau career as an acting assistant director, told NPR's Ryan Lucasthis week that "there's been plenty of controversies, but never accusations that the FBI has become a political tool for one party or another, or one set of political beliefs or another."

Never? Really?

In his defense, Swecker's FBI tenure coincides almost exactly with that of directors James Comey, Robert Mueller and Louis Freeh – who have held the top job since the mid-1990s. In these years, under these men, the FBI has been arguably less politicized and less of a political tool than at any time in its 109-year history.

But to use the word "never" when discussing the history of the FBI's service to a political party or to a set of political beliefs is to invite not only disbelief, but bitter derision.

Political since its inception

As a matter of reality, the FBI has been political from its outset. While it has always had an ethos of professionalism and objectivity and devotion to law – the people in charge of it and the people in charge of the administrations under which it has served have been as political and as partisan as it is possible to be.

One could say the idea of a federal agency for conducting criminal investigations has been political by definition, practically from its inception.

Let's talk about Teddy Roosevelt for a moment. He started the precursor agency called the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) way back in 1908. He did it because he wanted someone to look at the books of some of the country's largest and most powerful businesses, which he suspected of violating the anti-trust laws meant to rein in the activities of monopolies.

Similarly, when the bureau was tasked with finding German spies during the First World War, it could be called law enforcement — pure and simple. But what about when it went rounded up and detained citizens who had not yet registered for the draft? Or harassed political radicals of various stripes whom the administration saw as security risks for their unorthodox ideas?

Pursuing Nazis, gangsters, political favors and payback

In the 1920s, the old BOI had a role in the Teapot Dome scandal that would eventually send several officials of President Harding's administration to prison.

But its role was not so much in exposing the oil companies that paid bribes for access to government oil reserves. It was, rather, in investigating a senator who had exposed the scandal. That forced the BOI director of the time to resign, opening the door to a young officer who became the agency's head in 1924. His name was J. Edgar Hoover.

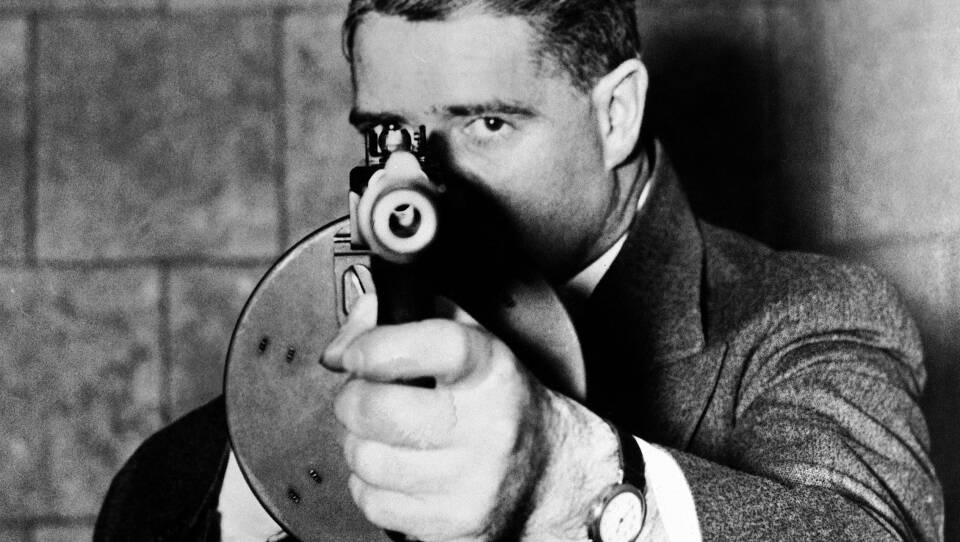

Thereafter, "the Feds" went after the heavily armed gangsters who sometimes terrorized the countryside and the urban landscape as well. Like the pursuit of spies, this work was broadly popular with the populace. Hoover proved effective at demythologizing folk heroes such as Charles "Pretty Boy" Floyd and George "Baby Face" Nelson, as well as at professionalizing the bureau itself. The idea of a crime lab solving crimes largely began with Hoover's agency, which added the word "federal" to its name in 1935.

Hoover's 48 years on the job included such popular crusades as rooting out Nazis during World War II but also such errands as collecting the names of people who wrote anti-war or isolationist letters to the White House. Hoover would eventually hold the top job through eight presidencies, doing various political favors for nearly all of them (according to evidence unearthed by a 1975 Senate investigation chaired by Idaho Sen. Frank Church).

During World War II, Hoover's bureau caught Nazi saboteurs and spies, but it also pursued people of Japanese descent and jailed those who objected. After the war, the bureau was prominent in pursuit of Communists, which came to mean a wide variety of people with divergent views.

And Hoover collaborated with the notorious blunderbuss Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy of Wisconsin, whose years of committee hearings wounded many reputations but wound up unmasking no actual Communists at all.

Plenty of Americans have regarded all these uses of the FBI's resources as entirely legitimate; plenty of others have found them entirely unacceptable. But you cannot argue they were not political. And in the hands of such figures as McCarthy or Richard Nixon, the FBI most definitely was a tool of one political party.

Rooting out "radicals," from Communists to war protest and civil rights leaders

Hoover's passion for rooting out radicals was formalized in what was called COINTELPRO (for counterintelligence program). Aimed originally at the Communist Party, the effort expanded to battle leftists in general and especially leaders of protests against the Vietnam War.

The program was also a scourge of the civil rights movement, most prominently the Rev. Martin Luther King. Hoover had a kind of obsession with King, hounding him for years — at one point sending him tape recordings of his tapped telephone and urging him to commit suicide.

At largely the same time, under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the FBI engaged in disruptive tactics against the Ku Klux Klan in the South. But after bloody riots erupted in many U.S. cities in the mid-1960s and later, Hoover turned his focus to "black nationalist" groups such as the Black Panthers, bringing disrepute and sewing dissent in its ranks.

Here again, the FBI was proving its worth to at least one concept of law enforcement even as it showed itself as a dangerous and repressive institution to others. But what one cannot deny was that it became a political tool – not just repeatedly but continually over many years.

Infamous unverified dossiers

Hoover also used his bureau to compile dossiers on people in government he thought might be security risks. These included hundreds of officials and bureaucrats he thought might be vulnerable to blackmail because they were gay. Hoover compiled mountains of evidence regarding people's sexual orientation, a store that was eventually destroyed by one of his successors in the 1970s – after Hoover's death.

At the same time, thousands of other Americans were able to get access to the files the FBI had kept on them and their activities for decades. Many of these records included totally unproven and unverified accusations included in "raw files" that were not meant for general release but available to various authorities at Hoover's discretion.

Another occasion of historical significance involving the FBI was the Watergate scandal and subsequent congressional and law enforcement action leading to Nixon's resignation as president in 1974.

Deep State déjà vu?

Watergate was happening just as the FBI was finally transitioning to a new director. Nixon appointed an outsider named L. Patrick Gray, who lasted less than a year. But during that period, the former No. 2 man in the bureau, W. Mark Felt, got wind of various forms of skulduggery practiced by Nixon's re-election campaign in 1971 and 1972, culminating in the burglary at the Watergate hotel that gave the scandal its name.

Felt managed to convey much of what he learned to a young reporter he knew who worked at The Washington Post. The reporter was Bob Woodward, and the rest is history — highly politicized history. Those who still defend Nixon today have to contend with the role played by Felt in forcing the congressional and legal proceedings that forced Nixon to resign in 1974.

Perhaps it is that episode in the long history of the bureau that is making some on Capitol Hill and some conservatives in the media uneasy about where the current investigation of Trump's campaign and cronies could be going. For these individuals, any indication that evidence gathered by the FBI could bring Trump or members of his circle to legal reckoning would be a bad case of déjà vu.

Copyright 2018 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.