Updated on Apr. 10, 2019

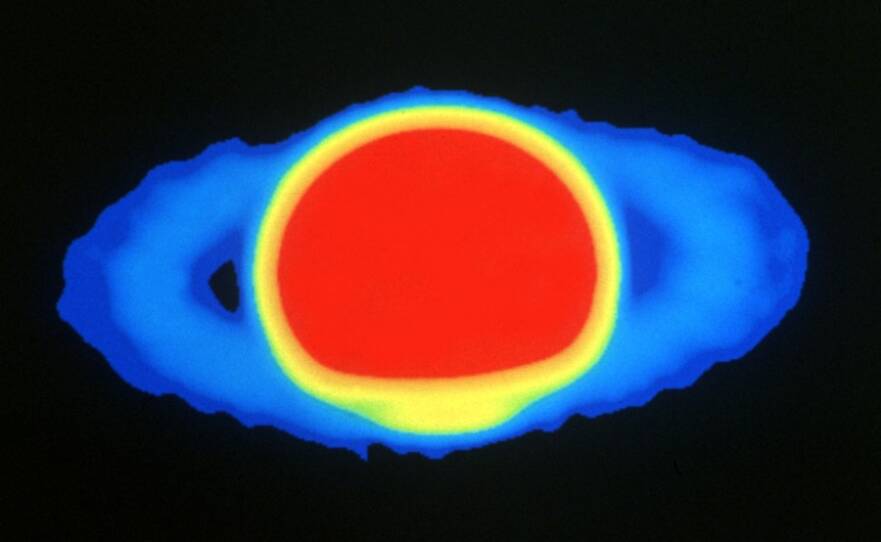

Scientists on Wednesday revealed the first image ever made of a black hole, depicting a fiery orange and black ring of gravity-twisted light swirling around the edges of the abyss.

Assembling data gathered by eight radio telescopes around the world, astronomers captured a picture of the hot, shadowy edges of a supermassive black hole, the light-sucking monsters of the universe theorized by Einstein more than a century ago and confirmed by observations for decades. It is along those edges that light bends around itself in a cosmic funhouse effect.

"We have seen what we thought was unseeable. We have seen and taken a picture of a black hole. Here it is," said Sheperd Doeleman of Harvard.

Ground zero for the project is right in our backyard, at MIT’s Haystack observatory in Westford. Two years ago, WGBH News' Edgar B. Herwick III visited the Haystack observatory to find out how it all worked. His original story is below.

Listen to the original story, published Apr. 5, 2017:

Right now, you may be reading this online or on your phone, but this story began as a broadcast on the radio.

And as Vincent Fish, research scientist at MIT Haystack Observatory in Westford, Mass. explained, our ability to broadcast sound over the air to your radio is thanks to — of all things — light.

"A common misconception is that radio waves are sound waves," he explained. "They are not. WGBH transmits a signal using radio waves, which is a form of light, a form of electromagnetic radiation."

This light is not visible to our eyes, but it is visible if you have the right tools: a radio telescope, for instance. Radio telescopes have allowed scientists like Dr. Fish to peer deep into space, and look at everything from planets to stars to distant galaxies.

"In essence, everything in the universe is a radio station," said Fish. "Everything emits radio waves or absorbs radio waves or interacts with them somehow."

But what about black holes, those mysterious entities thought to be at the center of all galaxies, including our own?

I heard that here at MIT Haystack, they were trying to capture an image of one of these elusive objects for the first time. It got me curious — is that even possible? Fish says yes, but suffice it to say, "You need a much bigger antenna than the one you have in your car."

How much bigger?

"We are basically building a telescope the size of the planet in order to see a black hole, because you need a telescope that large," said Michael Hecht, associate director for research management at MIT Haystack.

"It’s a mind-blowing adventure, what the human mind and the human imagination can do with technology and science and creativity."

This adventure is aptly called the Event Horizon Telescope. No light can escape a black hole, but what is visible is the light being pulled into it along its edge, an area called the event horizon.

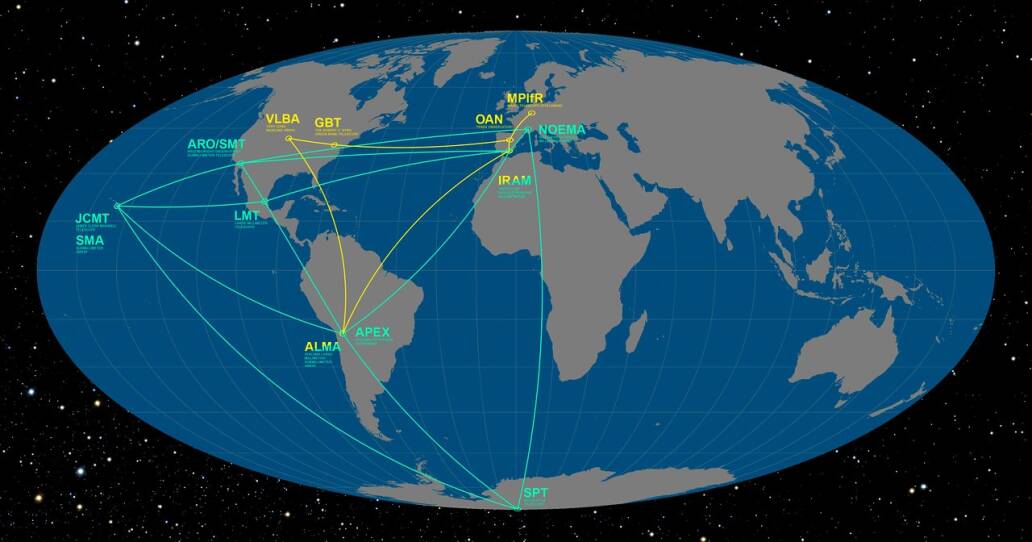

This "earth-sized" telescope is only virtually earth-sized. In reality, it is dozens of radio telescopes, scattered all across the planet, from Mauna Kea in Hawaii to Arizona, Mexico to Chile, and Spain to the South Pole.

Through a technique called interferometry, these various telescopes can be tied together, so to speak, and made to work as if they were one enormous, powerful, dish — with a resolving power 200 times than that of the Hubble Space Telescope.

That's a good thing, since Sagittarius-A, the black hole at the center of our galaxy, is 26,000 light years away.

Fish likened the task of capturing enough detail for an image to trying to take a picture from Earth of an orange on the surface of the moon, or reading the date off a coin from across the country.

Beginning April 5, the team has a 10-night window during which it hopes to get at least five nights of observations in, depending on the weather.

Along the way, a mind-spinning amount of highly detailed observational data will be recorded on hundreds of hard drives, and delivered right here to Haystack, where a powerful supercomputer called a correlator will go to work piecing it all together.

"The correlator acts like the lens of the event horizon telescope," said Fish. "We can make those signals recombine as if we had an earth-sized telescope."

It will take months for the correlator to crunch all the data, which is fine by the folks here at MIT Haystack, who have been preparing for this moment for years.

That includes research scientist Lynn Matthews, who was instrumental in getting the powerful ALMA telescope array in Chile into the fold.

"We’ve been working with ALMA over the last several years, getting 61 individual antennas together so they could function as one big light bucket," she said.

And it also includes Don Sousa, the man in charge of shipping and receiving all those hard drives.

"I’ve shipped stuff everywhere," Sousa said. "The South Pole, every continent, and I’ve never lost anything ... I shouldn’t say that without knocking on something."

The end result, the team hopes, will be the first-ever picture of a black hole. If captured, it could also offer scientists a chance to test the predictions of perhaps the most well-known person to ever work in their field.

"We want to see whether Einstein was right," said Fish. "This is something that people have been trying to do since the 19-teens, is test general relativity."

But it goes even deeper for Fish. He said that everyone from writers to philosophers to believers have sought to understand our place in the universe. And this is his chance to contribute to that age-old human quest.

"You let the universe reveal itself to you, and astronomy is just the scientific way of doing that," said Fish. After a brief pause he added, "Plus, it's cool."

The Associated Press contributed to this article.