Editor's note: The Environmental Protection Agency has approved the use of mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia bacteria as a "biopesticide" in 20 states and the District of Columbia. With this method, offspring of infected male mosquitoes die, which reduces the risk of mosquito-borne diseases. Back in 2012, NPR's Joe Palca wrote about scientist Scott O'Neill's 20 years of struggle to prove that infecting mosquitoes with Wolbachia could be used to fight disease. Here is his story.

This summer, my big idea is to explore the big ideas of science. Instead of just reporting science as results — the stuff that's published in scientific journals and covered as news — I want to take you inside the world of science. I hope I'll make it easier to understand how science works, and just how cool the process of discovery and innovation really is.

A lot of science involves failure, but there are also the brilliant successes, successes that can lead to new inventions, new tools, new drugs — things that can change the world

That got me thinking that I wanted to dive deeper into the story of an Australian scientist named Scott O'Neill. Scott had come up a clever new way for combating dengue fever.

Dengue is a terrible disease. It sickens tens of millions and kills tens of thousands. There's no cure, no vaccine and pretty much no way to prevent it. It's one of those diseases transmitted by a mosquito, like malaria.

About 20 years ago, a lot of scientists got excited about the idea of genetically modifying mosquitoes so they couldn't transmit these diseases. People are still pursuing this approach. But I thought genetically modifying mosquitoes would be really hard to do. Even if you were able to make these disease-blocking mosquitoes in the lab, I didn't see how you would ever get them to survive in the wild, and displace the disease-transmitting mosquitoes that were already there. There was also a societal problem with the scheme. Most people probably wouldn't be thrilled about having swarms of genetically modified mosquitoes released in their backyards.

But last summer, when I read about O'Neill's work, it really knocked me out. His big idea was to infect mosquitoes with a naturally occurring bacteria called Wolbachia. Turns out that by some unknown quirk of biology, Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes can't carry the dengue virus.

Let me repeat that, because this is a key point: A mosquito infected with the bacteria called Wolbachia can't transmit the virus that causes dengue. One microbe defeats the other.

When I interviewed O'Neill by phone last year, he told me the idea seemed to be working. He had released his Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes into two small communities in northeastern Australia.

"Over a very short period of time, the Wolbachia was able to invade the wild mosquito population until close to 100 percent of all mosquitoes had the Wolbachia infection — and so we presume, greatly reduced ability to transmit dengue between people," O'Neill told me.

That was enough success for me to do a short news story about O'Neill's work. But I knew there was more. I convinced my editor to let me go to Australia to learn more about O'Neill and his big idea.

'Incredibly Frustrating Work'

One of the first things I learned when I got to his lab at Monash University in Melbourne was a surprise: It had taken O'Neill 20 years to get his big idea to work.

"You know, I was incredibly persistent in not wanting to give this idea up," O'Neill said. "I thought the idea was a good idea, and I don't think you get too many ideas in your life, actually. At least I don't. I'm not smart enough. So I thought this idea was a really good idea."

The problem was that O'Neill couldn't figure out how to infect mosquitoes with Wolbachia. Remember, a Wolbachia infected mosquito can't transmit dengue.

You can't just spread Wolbachia bacteria around and hope the mosquitoes catch it. Instead, you have to puncture a mosquito egg or embryo about the size of a poppy seed with a hair-thin needle containing the bacteria, peering through a microscope the entire time so you can see what you're doing.

"It's incredibly frustrating work," O'Neill says.

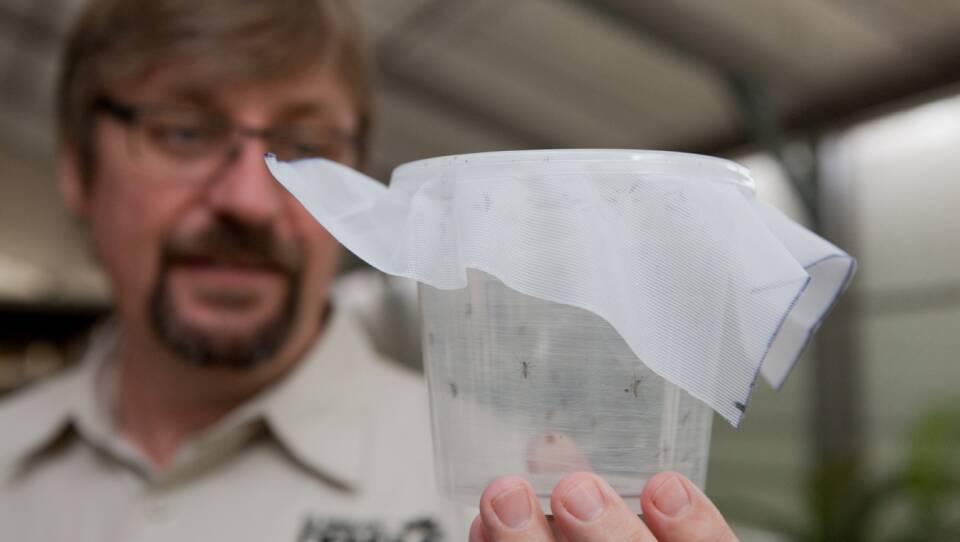

His colleague Tom Walker spends hour after hour, day after day, trying to inject the embryos. Even though he's become an expert at this, Walker can do no more than 500 a day.

Then the scientists have to wait a week until the adult mosquitoes emerge to see if any are infected with Wolbachia. Walker says in this latest round of work he's injected 18,000 eggs — with nothing to show for it. "The success rate is very low," says Walker, in something of an understatement.

"We don't have any windows that can open in this building, so people like Tom can't jump out of them," O'Neill adds with a laugh. He sounds like he's only half kidding.

The good news is that if you can manage to get the bacteria into even one mosquito, nature will take care of spreading it for you. Any mommy mosquito that's infected will also infect all her darling offspring, all 100 or more of them. And when those baby mosquitoes become mature in about 10 days, the new mommies among them will pass Wolbachia to their babies. Pretty soon, everybody who's anybody in that mosquito community is infected.

Success: 'A Significant Impact On Dengue Disease In Communities'

Now as I said, O'Neill has been pushing this idea of using Wolbachia to control dengue for decades, for a most of that time without any success. I asked him what it takes to stick with something for that long.

"I think being obsessive," he replied. "Being maybe a little ill in that regard. And it's just that I seem to have focused my obsession onto Wolbachia instead of on to postage stamps or model trains."

And even though his obsession has brought him to the point where he's shown he can get his Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes to spread in the wild, that's not the success he's ultimately after. "Success for me is having a significant impact on dengue disease in communities," he says.

To do that, he'll have to release his mosquitoes in a place where there's a lot of dengue, and then see if that brings down the number of cases of the disease in humans. Those studies are being planned now.

The stakes are high. By some estimates, more than a billion people around the world are at risk for getting dengue. Even if it doesn't kill you, I'm told a case of dengue can make you feel so bad, you wish you were dead.

"[It's] pretty much the worst disease I've ever had. It was not fun," says Steven Williams, a tropical disease researcher at Smith College in Northampton, Mass. Williams was bitten by a dengue mosquito while on a trip to French Polynesia. He says for 10 days he had a high fever, horrible headache and terrible pain in his muscles and joints.

One other delightful thing about dengue: There are no specific drugs to treat it. "You basically just have to ride it out," says Williams.

Moments Of Triumph, With Trepidation

With no cure and no vaccine, O'Neill's Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes could make a huge difference. Although proving that is still years off, there have been moments of triumph in the 20-year slog that's brought him this far.

Take the day in 2006, when one of O'Neill's graduate students told him he thought he'd finally succeeded in infecting a dengue mosquito with Wolbachia.

I figured this must have been a red-letter day for O'Neill, a day of sheer elation. He told me looking back on it, it was. But at the time it didn't seem that way.

"Because ... you're so used to failure, and you don't believe anything when you see it," he says. "And so you can think back to when there was a eureka moment, but at the time, it's probably ... 'This looks pretty good but, you know, I've been burnt thousands of times before. Let's go and do it again, and let's do it another time, and check and check and check, and make sure it's actually real.' "

O'Neill says the day his team really enjoyed was last year when they tested to see if their mosquitoes would take over from the other mosquitoes in the wild.

O'Neill's colleague Scott Ritchie recorded the event for posterity on his cellphone.

That got me interested in O'Neill's work last summer. He and his colleagues have now completed a second release, and the results are looking promising. But O'Neill says it's not yet time to celebrate.

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.