During the last few weeks of August, Torri Hayslett's room at McKinley Technology High School feels more like an accountant's office than a college adviser's.

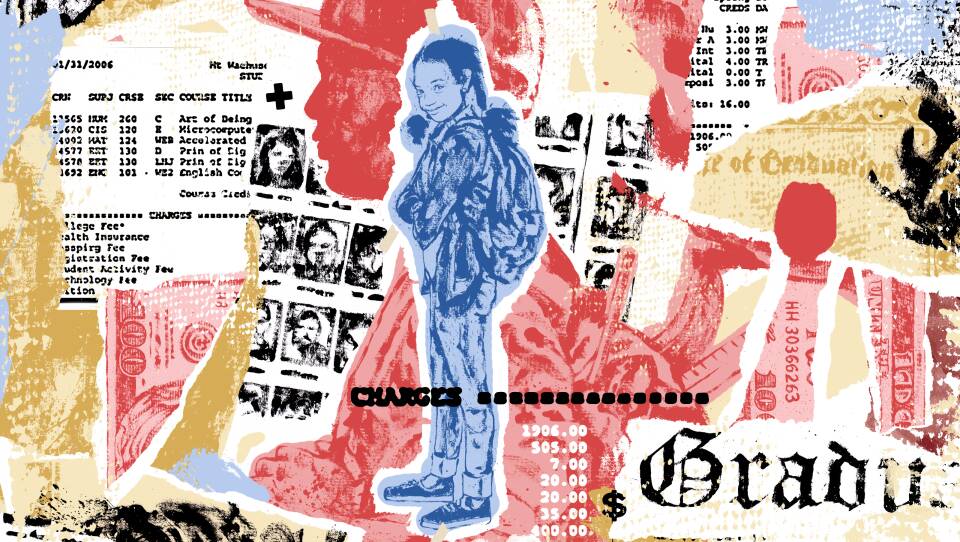

"Thirty-one thousand dollars minus $4,000, minus $2,500," she says, saying the numbers out loud before punching them into the calculator. She's sitting with one of her students, who recently graduated from McKinley. They're looking over her first college bill.

"Does the $9,000 include the $3,000?" Hayslett asks. "I think that is including," the student responds. "Again, I do not know a lot of logistics right now."

Hayslett works as a college and career manager, helping nearly 150 seniors at this public high school in Washington, D.C. Nearly 40 percent of McKinley's students come from low-income families.

She says this is what happens in July and August: Seniors who've already graduated come to her office (or call or text) trying to get a handle on all these numbers.

Many of the students who shuffle into her office ended the school year in celebration. They're going to college! The schools they've picked were pinned up on bulletin boards in the hall; some students even made the local news.

And then summer rolls around, bringing with it one big question: Can I actually afford this?

"It still doesn't become a reality until they see those numbers on a piece of paper and it doesn't balance out," says Hayslett.

This last-minute money scramble is one of the main reasons that nearly a third of low-income students with college-going plans never start freshman year.

This past spring, every graduating member of the senior class at McKinley Tech was accepted to college, Hayslett tells me. But she works year-round, so her work didn't stop after graduation. She knows that only about 75 percent of those students will start classes in the fall.

Over the summer weeks, I visited Hayslett several times in her office. I saw her solve a range of problems: A homeless student was short several thousand dollars and hadn't yet received housing on campus. Hayslett borrowed a car and drove the student an hour north to Baltimore in order to talk face-to-face with the director of financial aid. While they were there, she helped secure the extra money he needed — plus a year-round dorm, so he won't have to sleep on someone's couch over winter break.

Another student's gap — about $6,000 — was filled when Hayslett ran into a local dentist when she was out with some friends. It turned out that one of his employees was that student's mom. The dentist made the connection and asked how the student's college plans were going. When Hayslett mentioned they were applying for last-minute scholarships, the dentist offered to help. He's now paying that $6,000.

Sometimes, Hayslett will pay the difference herself. When a student needed just $250 for a housing deposit, she covered it.

"I know I can't do that for every student," she says, "but sometimes it can just make such a big difference." She also gets her friends and family to chip in. "I'm not above asking anyone for college money for these students," she says. That includes local celebrities. This year, she helped students needing college money write personal letters, which she mailed to anyone she could find addresses for, including actress Taraji P. Henson.

One of her students, Damoni Tolson, planned on going to Johnson & Wales University, a private college with a campus in Florida. Ever since he was a kid, he'd wanted to make his way to Florida — he'd gotten a good scholarship in March. (Later it would turn out that he'd gotten the highest amount of scholarship money the school could give, because Johnson & Wales doesn't give full-rides.)

And yet, in the last week of August, he was still about $12,000 short. His mom was having trouble getting a loan. And so, with the days counting down, he found himself in Hayslett's office, facing a tough decision.

Hayslett turns to Damoni, cutting right to it: Do you want to consider going to another school?

"We can see," he says, looking down at his feet. "I don't really want to switch this decision this late in, but if the loan doesn't go through, I don't really have any other options."

Most students in Damoni's position have limited options. They can sit out for a semester, while they get finances in order. Or they can see if they can get in somewhere else.

Often, spots at local community colleges are still available, and some state programs have rolling admission. Though for both options, much of the scholarship money has already been given out to other students.

It can be really disheartening, says Shaquinah Wright, who oversees College Bridge, a program in New York City that pairs current college students with high school seniors in order to support them through the college process.

"These are young people who haven't figured it all out, and they're not supposed to," she says. "The finish line keeps getting further and further away."

Experts say there are things that can help: High school students can select smarter college choices. Colleges and universities can send clearer financial-award letters. And high schools can support students over the summer with year-round college counselors, like Torri Hayslett.

Damoni has some advice for current seniors, too: "When you're applying to schools, make sure you have an idea of what you're willing to spend," he says. "Come up with a plan with your parents, to make sure everything is good financially, so when the time comes, you're not forced into anything."

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/ .