Cathy Malkasian creates fantastic worlds out of her proprietary blend of melancholy and dream-logic, and peoples them with characters who are all too dully, achingly human. Her landscapes and cityscapes, rendered in gorgeous colored pencils, can seem as chilly and remote as her facial expressions seem warm and intimate.

In graphic novels like Temperance, about the lies that the citizens of a walled-off city tell themselves, and in her two Percy Gloom books, a gentle absurdism asserts itself so quietly that story elements like talking goats and heads that glow come off like prosaic details.

That's important, because without a sense of assured, implacable groundedness, Malkasian's narratives could easily feel labored, built as they are on such baroque, involuted infrastructure.

To wit: the opening pages of Eartha, Malkasian's latest, ask the reader to unpack a series of high-concept premises, any one of which could form the basis of its own book:

1. Eartha, "big as a boulder and softer than the moss that grew on it," lives in Echo Fjord, a bucolic land and whose citizens harvest dreams.

2. Said dreams belong to the residents of a faraway city.

3. The dreams that grow out of the ground are detained, and a thick paste called shadow applied to them, to keep them from floating away.

4. The dreams' minders touch the dreams to provide "a boost of energy to ignite them back into themselves."

5. The dreams then scamper through Echo Fjord toward a doorway, giving off brilliant rays of light out of the top of their heads.

6. As they pass through the doorway, they dissolve, having achieved their purpose.

That's ... a lot to take in, granted, but Malkasian is so careful and considered in rendering the array of dreams (the sad, the joyous, the horny and the hateful) that we don't notice how much narrative work she's doing.

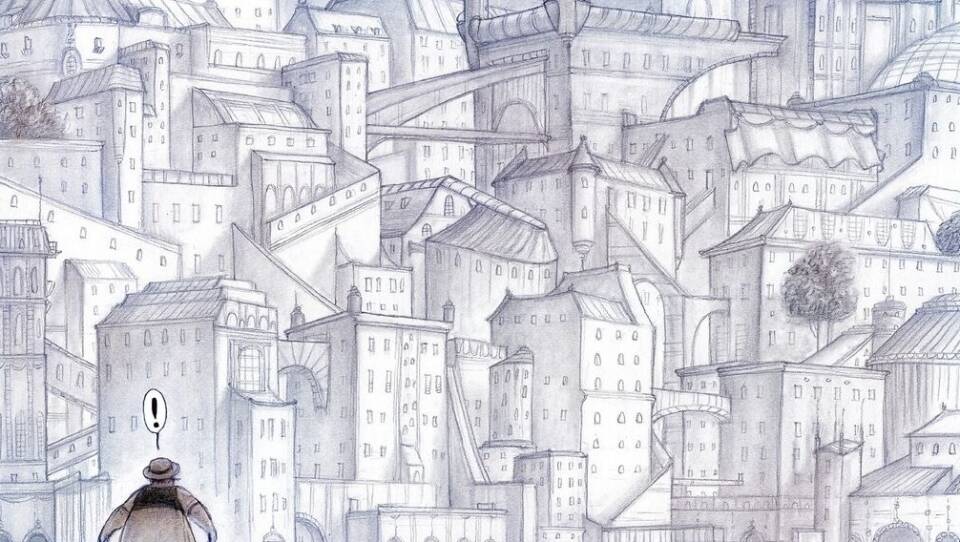

In the pages that follow, Eartha will depart her homeland to make her way to the nameless city, where she — and we — will meet the men and women who sent those dreams to her people across the vast sea. Unguessed-at connections among them will come to light; insights gained in those opening pages will aid Eartha in her quest (as will a talking cat, an intoxicating plum tree, and an old woman who knows more than she's letting on).

Such steel-trap plotting is something new from Malkasian, whose previous graphic novels have felt free to abandon familiar storytelling structure to double-down on some surreal image or theme. She's consistently shown an eagerness to walk the line between fabulist fiction and social satire, and Eartha is no different: the city's residents are addicted to biscuits printed with headlines of lurid tragedy ("Sinister Dandruff Muzzle Hen! Septic Jackass Gambles Naked! Prominent Orgy Provokes Rabies!"), and are ruled by thuggish, Mussolini-like figures who encourage the populace to embrace dull-eyed cynicism and performative despair.

Eartha will win the day, of course, because she maintains the ability to feel, and dream, and her sense of fairness will protect her from the city's corrupt politicians and its emotionally bankrupt fascination with the ugliness of life.

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.