Here at the Curiosity Desk, we love to dig back thorough the annals of history. And, you know, we tend to think about history on particular days, because of single (and singular) moments – like April 19th thanks to those first shots at Lexington and Concord or July 4th thanks to the signing (or more accurately the adoption) of the Declaration of Independence.

But today I'd like to make the case for, well, today: March 22. Not because of one event, but three of them, separated by decades, that I believe demonstrate the evolution of not just Massachusetts, but America. Does my argument hold water? You be the judge.

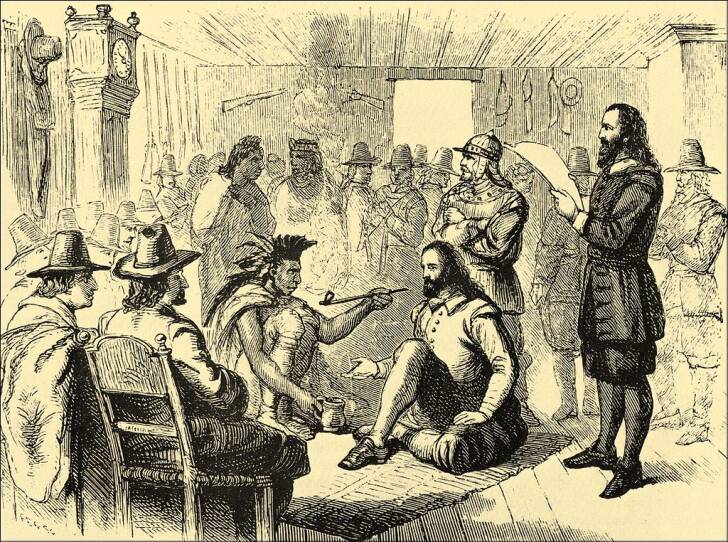

Exhibit A: 1621

Only about 50 of the Pilgrims who arrived in the New World the previous year survived the winter. As Richard Pickering, deputy executive director for Plimoth Plantation explains, they were strangers in a strange land.

"The English come into a world where they don’t speak the language of the indigenous peoples," he said.

On March 22, the Wampanoag chief Massasoit reached out to the newcomers, and suggested something extraordinary: a mutual alliance. It was a shrewd move that allowed the chief to position himself in the new political world of southern New England.

Massasoit gained new trading partners and access to English military technology. But you could argue the colonists got much more. The Wampanoag taught them how to grow corn, served as translators, and brokered relations with as many as a dozen other area tribes. In short, the agreement allowed the fledgling colony to not only survive, but flourish in those crucial early decades.

"It was one of the exemplary agreements made between the colonizers and native peoples that established a stability that lasted so long," said Pickering. "You didn’t find that in the other British American colonies."

The agreement of March 22 was reaffirmed later that same year with a feast that we still celebrate today as the first Thanksgiving.

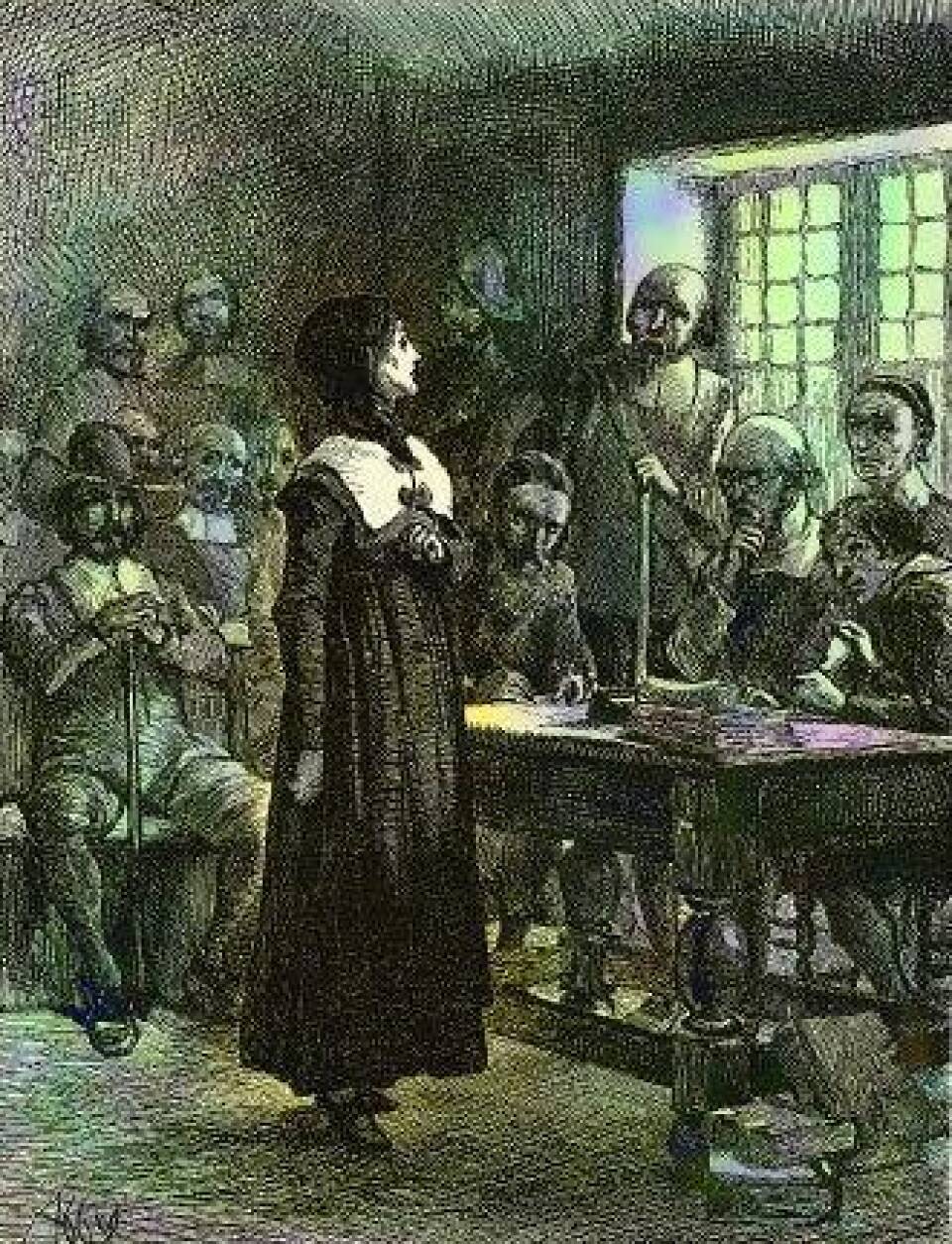

Exhibit B: 1638

By now, some 20,000 English are in Massachusetts, most of them engaged in the Puritan experiment that was the Massachusetts Bay colony. The once small community was now facing growing pains, and challengers from within like Anne Hutchinson.

"She was part of, and a leader of, what started as a kind of religious movement in the colony that turned into a near political civil war," said historian and scholar Lori Stokes.

The Puritans, with their curious mix of religious and civil governance, had brought Hutchinson to trial for challenging the ministers’ interpretation of the faith and, by extension, their authority.

"I am above the law," Stokes said, explaining Hutchinson's position. "I’m not going to be tried by you people. You’re not going to decide my fate. God will decide my fate."

Hutchinson was ultimately banished from the colony, effective March 22.

In the Hutchinson affair, Stokes says we see the emergence of themes that would become hallmarks of the American experience: the challenge of self-governance at scale, the conflict between religious and civil authority, and the balance of the rule of law with the rule of men.

"We have those two things conflicting, and it’s almost like the yin and yang of our nation," she said. "We believe in government and then we also believe in these charismatic departures from government and we swing back and forth between them.

Exhibit C: 1765

Massachusetts is now home to hundreds of thousands of colonists. And March 22 again become significant, when the British Parliament passes the Stamp Act. Looking to recoup the money spent on the French and Indian Wars, they levied a tax on everything from playing cards to newspapers to legal and trade documents. The colonists had no say in the law’s passage, and were less than thrilled with it.

"They went to demonstrations, they had what they called later the Stamp Act riots, set fire to effigies of the different members of Parliament who affected this," explained Stephen Chueka, creative department supervisor at the Boston Tea Party Ships and Museum.

The catchphrase that grew out of the protests, "No taxation without representation," showed that, despite the unrest, the colonists were fighting not yet for independence, but simply for a voice at the table.

"We are a part of this empire as much as anyone else," said Chueka, describing the colonists' sentiment at the time. "As much as any Irishman, Scotsman, a man born in London, Liverpool, you name it. We are like them. We deserve all the equal rights and privileges you have."

Despite the fact that the Stamp Act was repealed the next year, the taxes kept on coming, culminating in the Tea Act, the Boston Tea Party and the push for Independence.

"Then it’s gone too far to recede as they say," explained Chueka. "Even though as we head into '74, '75 they’re still trying to find that peaceful arrangement, at the same time we’re readying guns and ammunition in the countryside for any inevitable conflict."

That conflict, of course, came as did the irrevocable break with England that we celebrate each July 4th as the birth of our nation. But the path to that moment was as winding as it was incremental; the result of countless decisions, turning points and events, including three which – by coincidence of history – all occurred on March 22.

We love those tales of hidden and forgotten Massachusetts history here at the Curiosity Desk. If you have one to share, let us know.