With stages spread throughout the Harvard Athletic Complex transforming soccer fields to midways, our city’s festival has grown up. Progress toward the organizers’ avowed goal of having a festival that matches the scale of a Coachella or a Lollapalooza proceeds apace. This year’s Boston Calling featured a third stage — christened by Mac DeMarco’ s barefoot crowd-surfing — and a full-on comedy arena. And while the fête took a shift toward the electronic and the dance-oriented last year, this time around the lineup looked toward the eclectic, with nods toward contemporary hip hop, Americana, and bona fide prog metal in Sunday’s headliner, Tool .

The diversity of the festival lineup served to underscore the main issue with Boston Calling 2.0: this new version of the festival doesn’t know what it is yet. While Boston Calling’s city hall era ended last year with one of the most assured, well-organized, and well-conceived iterations of the festival, its Allston era kicked off with a carnivalesque atmosphere, marred by a lamentable lack of planning to handle the crowd of over 40,000 attendees. Lines abounded from food stand to beer vendor and right back through the admission gates. The labyrinthine setup confused concertgoers, and created bottlenecks along routes from stage to stage.

Watching the throng tromp along muddied paths, eroding new walkways where sod had evidently been lain for Harvard’s athletic seasons, I couldn’t help but wonder just how much revenue is headed the Crimson’s way to host the festival. Surely, the littered playing surfaces and damaged fences were taken into consideration before allowing Boston Calling to set up shop along the Charles. But to this degree? It’d be hard to imagine.

With some days passed since the festival end, a few of Front Row’s writers share their thoughts on this year’s festival, starting with day one:

Friday, May 26th

Lucy Dacus looked out on a damp crowd midway through her set on the first day of Boston Calling, and let us in on a little fear she’d been harboring. “I expected to see Chance the Rapper fans, but some of you know the words. Thank you for caring.” During an interview later in the day, Dacus told us that opening the festival’s green stage — where Chance would headline later that evening — was a daunting task. She feared a sea of Chance’s trademark “3” caps in front of the stage, but while there were certainly enough Chance caps to go around, there was a contingent there to hear Dacus.

More importantly, Dacus reminded us that increasingly festivalized touring circuits over the past ten years have created challenges for early career and mid-level artists that haven’t made their way to headliner status. Is there an audience for them? And if so, who is that audience? “I don’t really know my own audience. Sure, people show up and surprise me and the first five rows might be super into it. But I still see it as the crowd of the people that are coming after us,” Dacus said. The pleasant surprise of hearing more than a few folks singing along to her more well-known tunes — a roar went up when Dacus performed her indie radio hit, “I Don’t Want to Be Funny Anymore” — made Dacus feel confident and comfortable on stage, and her set showed her as the season performer she’s become since we last wrote about her for a support set last year at the Middle East .

For a group like Xylouris White , the avant garde jazz-influenced post-rock duo (did we mention eclecticism in this year’s programming?), the audience seemed to be at the periphery of their attention. The spontaneous dialogic grooves fashioned by lautist George Xylouris and drummer Jim White washed over the sparse crowd gathered under a misting rain. Their crowd was transient, but the band had a pronounced effect on the earliest attendees. The folks shuffling to and from the blue stage early on looked equal parts puzzled and delighted.

Such responses to Dacus and Xylouris White underscored the theme for the first day of the festival: what’s going on here? While audiences scrambled to simply get in the gates, and to make it to appointed sets on time, the acts provided a wide-ranging stylistic sampler for the opening audience.

Chicago-sourced Whitney rides the crest of post-Laurel Canyon beard rockers like Dawes and Father John Misty, yet extends to a sound more obscure and yet more accessible. Not many in the crowd seemed familiar with the band, so while a few gray-haired fans of the Byrds and the Band slid past me to indulge Whitney’s take on 1970s AM country rock, a couple of post-ironic scenesters ambled past muttering, “I can’t believe they got Whitney Houston to come to the show.” Nevertheless, Whitney made the uncool cool again, with soul-tinged arrangements that bordered on Chuck Mangione schmaltz, but reeled things in to keep the better part of the crowd grooving.

Two things struck me about the crowd about midway through day one. First, despite his status as a middle-of-the-order festival act, Mac DeMarco had brought out a slacker army replete with flat-brimmed olive drab caps that was second only to Chance the Rapper’s crowd. Second, the number of White Sox jerseys and conversations about Chicago made me wonder if I was in the right city. At the end of last year’s festival, we wondered if Boston Calling would lose a little civic identity with its move to Harvard’s Athletic Complex? For a few moments during Whitney’s set, it seemed we’d moved to the banks of Lake Michigan. I wondered maybe this wasn’t Chicago Calling? If Boston Calling aspires to be in the mode of a Coachella or a Lollapalooza, the increasing facelessness of this festival seemed to put it well on its way.

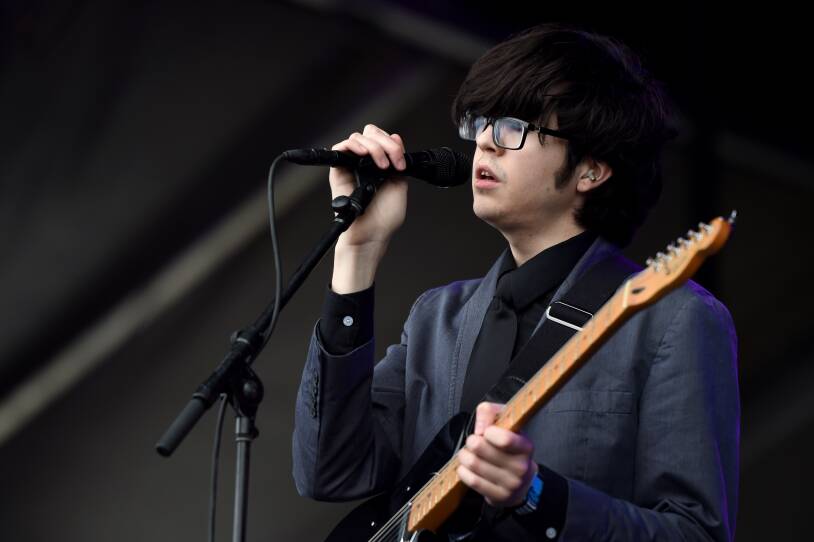

Though much of the first day was pleasant, nothing marked the experience of Boston Calling as “right here, right now.” Deerhoof ’s ethereal showers glided over the festival grounds with jagged strokes of metallic dissonance reaching down to keep us awake. Sylvan Esso celebrated the end of the (first) rain with bouncy dance grooves. And Car Seat Headrest ’s confessional songwriting generated intense moments of intimacy one does not often witness in a crowd of a few thousand.

Atlanta trio Migos — made a duo without missing member Offset — kicked off the hip hop program of the weekend. The group could have rode a wave of momentum from Sylvan Esso’s set with much of the crowd ambling from the red stage over to the green, but DJ Durel’s twenty minutes of hype, replete with teases of Migos’ tunes, wore thin for those of us in the back. By the time Quavo and Takeoff took the stage, the transient slice of the audience wandered off to get some food, catch some comedy, or hear Mac DeMarco. Migos stayed with us, though, with an abiding bass echoing across the entire festival grounds.

Though Mac DeMarco’s crowd rivaled Migos’ in the number of joints being rolled and bowls being concealed, it went for a different effect. DeMarco’s slacker vibe rode across the crowd, in what was the first veritable festival performance of the day. DeMarco played the host to girls on shoulders, lighters, bras, and hats tossed on stage, and the most legitimate crowd surfing this side of the 1990s. What did DeMarco sound like? That wasn’t the point. Mac DeMarco’s slob spectacle was one of the most intriguing parts of the festival. He took the more intimate tracks of his latest, This Old Dog, and ramped them up not with a dynamic sensibility or musical pretense, but with an antic-laden stage show that was nothing if not compelling.

The dash from blue to red stage for Bon Iver ’s set was a mud-mashing slosh ending at an ill-considered and downright boring set from Justin Vernon. Vernon traded on the slacker cred of DeMarco and his crowd, appearing on stage slovenly bearded with flat-brimmed Baltimore Orioles cap. DeMarco read as gripping in his utter lack of pretense; Bon Iver read as nothing but pretense, treating every musical whim with a delicacy and preciousness that eventually led to an overwrought jumble. When Bon Iver’s turn toward the electronic on his 2011 eponymous release echoed late-stage Genesis and offshoots like Mike and the Mechanics, many of his early supporters — myself included — poo-poohed a temporary misstep by an inventive and promising artist. Unfortunately, if Friday night’s set proved anything, it’s that the real Bon Iver is not the vulnerable artisan of flawed, but sublime tracks like “Skinny Love,” but instead the affected purveyor of dream pop nostalgic for the fabricated intimacy of late 80s soft pop.

Sigur Rós closed the blue stage on Friday with a resonant thrum that overpowered the echoing metallic manufacture of Bon Iver from across the festival midway. Stepping out from a light-wrought, gilded cage, the Icelandic trio washed the audience in flanged percussion and trademark bowed guitars. A good part of the audience skittered away when the skies opened yet again, while others made their way back to Chance’s set. But Sigur Rós’s set just worked, amplified by the darkened skies, and ebbing rain.

And then there was Chance, who kept the audience waiting fifteen minutes before crashing the stage on a tiny motorbike, accompanied by strobing pyrotechnics. There was a bit of a debate in the media tent afterwards regarding Chance’s choice of booming pyrotechnics just days after the horrific bombing in Manchester, but Chance’s energy and effervescent engagement with an otherwise sleepy audience after Bon Iver (or entranced if they’d made their way from Sigur Rós) provided a lesson in stagecraft.

Chance took Boston Calling to church, opening with “Mixtape” from his latest, Coloring Book, before moving on to rich takes on “All We Got” and an intimate performance of “Same Drugs” from a relocated stage beyond the sound board. Thirdstory’s choral accompaniment, Chance’s call and response with the audience, and a persistent technicolor ebullience from the stage elevated the 40,000 plus to a place beyond themselves. Chance paid homage to mentors, to place, and to fortune with his set, turning out an ode to the eclecticism and vacillating identity of this festival, giving us all a bit of focus to round out day one.