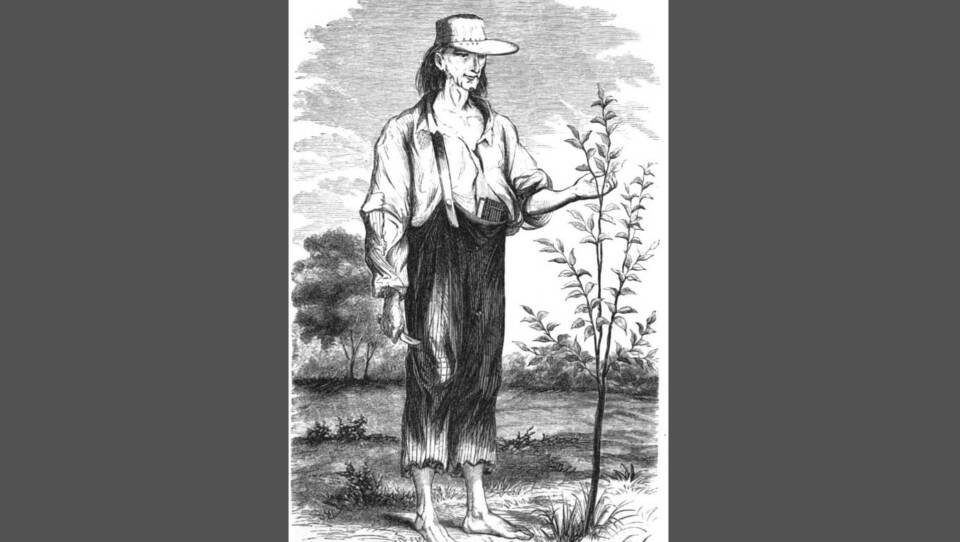

True story: In the early 1800s, Leominster, MA native John Chapman traveled America’s frontier barefoot, planting apple seeds. Most of us can say we’ve heard of Johnny Appleseed, as he was dubbed, but we are perhaps less familiar with what happened next.

Do You Know The Apple Man?

Chapman, intrepid entrepreneur that he was, sold his developing orchards to settlers coming in behind him. Faced with an often unforgiving landscape, where food was hard-earned, early settlers coveted these trees. The part of Johnny Appleseed’s story that’s often left out is that the apples on his trees were, for the most part, inedible.

The thrilling thing about planting an apple seed, is you never know what you might get. What you won’t end up with is a replica of the tree it came from because apple trees don’t grow true from seed. In other words, that seed won’t contain all the genetic material needed to reproduce a tree bearing comparable fruit. The only way to replicate the apples from your prize honeycrisp tree, for example, is to graft it–take a shoot or “scion” from the favored tree, and bond it to a compatible rootstock.

So, back to Johnny; though he knew about grafting–the technique had been around since the Romans–he was a devout Christian, a member of the Swedenborgian Church, who did not consider grafting to be in line with God’s plan, and believed that it caused plants suffering.

Whatever he was expecting, the vast majority of seeds he sowed blossomed into squat little crab apple trees bearing hard, bitter fruit.

Thoreau, perhaps, put it best in his 1862 essay Wild Apples, when he described apples grown from seed as “sour enough to set a squirrel’s teeth on edge and make a jay scream.” It all worked out just fine for the settlers who, with a scarcity of potable water, were more interested in making cider with apples than anything else. Crab apples were just fine for pressing into the drink, and fermentation took the edge off the hardships of frontier life.

It’s not to say there were no gems that sprouted from Chapmans’s endeavors. Perchance, by genetic lottery, a seed he planted yielded an apple tree with tasty fruit. The Golden Delicious, in fact, is thought to have sprung from the Grimes Golden, an apple discovered in West Virginia and most likely one of Chapman’s “offspring”. The Red Delicious, too, is generally agreed upon to be a descendant of his trees.

The Taming of the Apple

The apples we buy in the grocery store today are mostly cultivars, apples selectively bred from a pleasing tasting apple often found by chance in an orchard of crab apple trees, possibly centuries ago. Remarkably, that granny smith apple you might have sitting on your kitchen counter is actually a graft of a graft of a graft, etc., of that first chance seedling discovered by Mrs. Smith in New South Wales Australia, in 1868.

Put in the context of ‘apple-time,’ however, the Granny Smith is a veritable newborn. It was 4.5 million years ago, long before recorded history–to be fair, humans had only recently split off from apes–that Malus sieversii hung from the branches of a tree in the mountains of central Asia, in Kazakhstan. This wild apple, the ancestor of our domesticated apples, has given rise, over the ages, to countless thousands of apple varieties, with an infinite array textures and flavors.

1600 saw the first apples in the Americas; colonists arrived in Jamestown with their favorite apple grafts, but the harsh climate ensured that few of these survived. So, the discovery of a good apple on one’s land could be a great boon to a colonist farmer, who would waste little time grafting a bud from said tree and christening a new apple variety with often heartfelt expressiveness. Seek No Further, Virgil, Maiden’s Blush, Rome Beauty, Hidden Rose, Yellow Transparent, and Ashmead’s Kernel, were just a handful of the 15,000 different apple types in production in the U.S., by the early 1800s.

Then along came mass production and, no friend to variety, it favored apples with select virtues, for example, those that bore fruit annually versus biennially; those that were more pest-resistant; or those that stored and shipped well; and of course the more attractive-looking specimens. Gradually, the rich diversity of apples trickled down to the twenty or so familiar apple types that we’d recognize in orchards, and in our stores today.

Apple Lovers Rejoice

Happily some trees live to a ripe old age, even hundreds of years. So, here and there, perhaps in the corners of long-neglected fields, former orchards, and old growth forest, heirloom apple trees prevail. Today, more and more are being rediscovered; apple enthusiasts are giving them a new lease on life in craft ciders, artisanal restaurants, and farmers markets. New England apples like the Baldwin, Northern Spy, Rhode Island Greening, and Maine’s beautiful plum-colored Black Oxford are just some of these “forgotten apples,” that may have lost ground to more commercial apples in past years, but are making a comeback.

Boston can claim as its own the oldest of these heritage apples: the Roxbury Russet. That’s right, straight from Roxbury, where in 1635 a chance seedling sprouted in an orchard. The first named apple variety in the United States, the Roxbury Russet boasts a crisp tartness, sweetened with subtle traces of honey, lemonade, and pineapple, and was a favorite of Thomas Jefferson who grew “russettings,” as he called them, at Monticello. The apple also stored well in those pre-refrigeration days, and the dense flesh meant that it kept its shape in pies and tarts.

No one knows this better than Jason Bond, artisan chef at Bondir, in Cambridge and Concord. Committed to finding rare, interesting, local flavors for the dishes he creates, Bond hails the Roxbury Russet for its tang, its texture, and its firmness. Walk into Bondir today, and you might find a Roxbury Russet apple on the dessert menu, poached in buttermilk, with nutmeg and a homemade herb salt, and served with a fresh nettle cheese. Previous Bondir menus might have seen the Rhode Island Greening paired with a Tautog (blackfish) and turnips, or Gravenstein apples puréed into a custardy sorbet.

Other local foodies are also catching on. Once, the favorite apple for cider-making, Roxbury Russets were an obvious choice for one of the Artifact Cider Project’s signature drinks, named appropriately, ‘Roxbury’. The company, located in Everett, MA, was founded by Soham Bhatt and Jake Mazar, who are devoted to reinvigorating interest in regional produce and finding the next great apple.

It’s certainly curious to think that somewhere out there, off the beaten path, could be an antique apple tree waiting to be discovered, with distinctly unique tasting apples, courtesy of a barefoot wanderer with a sack of seeds.