Paris Alston: This is GBH's Morning Edition. On Valentine's Day 1868, Louisa May Alcott wrote in her diary about an article she was working on for the column Advice for Young Women.

Sarah Gristwood (Previously recorded): It was about old maids. Happy women was the title, and I put in my list all the busy, useful, independent spinsters I know. For liberty is a better husband than love to many of us. This was a nice little episode in my trials of an authoress, so I recorded.

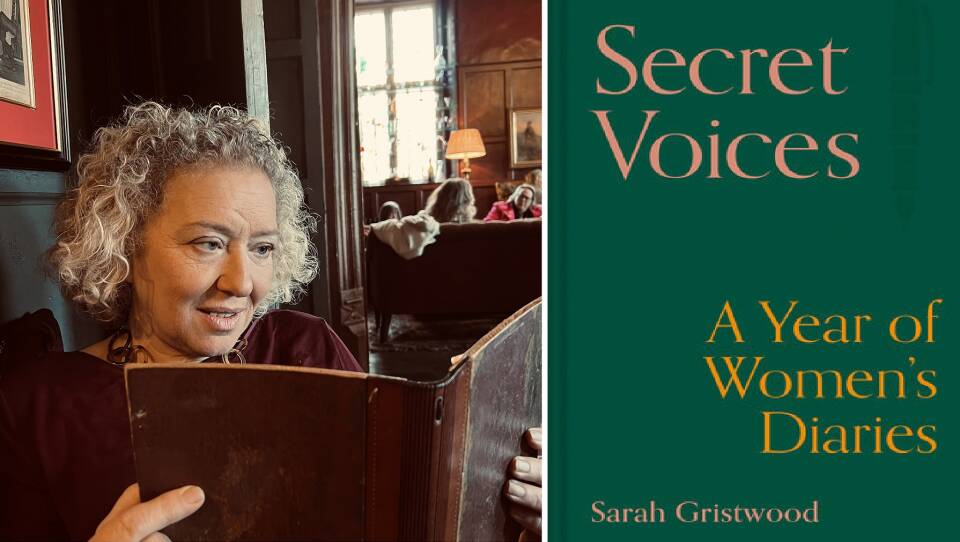

Alston: Now, of course, that is not her reading. That's author Sarah Gristwood. She's compiled Alcott's entry and hundreds of others written by other women diarists over a span of 400 years into a new book called "Secret Voices." I recently spoke to Gristwood about the importance of sharing these perspectives, and she explained how, for centuries, the diary or journal was one of the few places women could air such sentiments.

Gristwood: I think the thing that most surprised me was how often the dilemmas that we think of as modern ones were echoed hundreds of years back. Two hundred years ago and more, you get, for example, Elizabeth Fry, a Quaker great prison reformer, writing about how worried she was that her husband and her, I think it was 11 children, distracted her from what she thought of as her mission, her work. Well, juggling her career and family? That one hasn't exactly gone away today, has it?

Alston: Why did these diaries have to be kept a secret?

Gristwood: Some of these women, like Queen Victoria, must have known that there'd be public interest in her diaries. Other people might read them someday. Virginia Woolf, to professional writers. But even those women, I think, use their diaries to voice feelings that weren't acceptable in their own day: Anger. Ambition. Frustration. A Bostonian, Caroline Healey Dall, writes about the fear of the coming childbirth. We can all understand that, heaven knows. But it wasn't the kind of thing you were supposed to say out loud.

Alston: For some of the women, keeping their diaries and their feelings and thoughts a secret was a matter of survival. I'm thinking about the excerpts that are included from Anne Frank, who obviously was enduring horrific things, not knowing what her fate would be. Did you think about what we could be reading years from now, and diaries that are currently being kept not just by women, but women who are suffering various injustices and in conflicts around the world today?

Gristwood: Yes, absolutely. But that leads on to a very interesting question, which is whether the diary now is only the pen and paper or even the keyboard, or even whether you speak it onto tape, say. I do wonder to what degree social media is a new form of diary, all the little happenings of every day. If you want to remember what you were doing, maybe voice some unpopular opinions, you turn to X, Instagram, whatever.

Alston: Do you think we lose something when the diary goes public in that way?

Gristwood: Maybe. Or maybe we gain something as well. After all, traditionally the written diary, well, first of all, you've had to be able to write and also and to afford paper and pen. But also you had to be someone whose diary was kept, whether by a loving family or by some sort of library or trust if you were. But reading some of these extracts, I can't easily imagine anything I see on my social media feeds being quite that lovely.

Alston: That was Sarah Gristwood, author of "Secret Voices: A Year of Women's Diaries." Now, before I said goodbye, I had to ask her a very important question. I must ask you, as someone who's kept diaries and journals since I was a little girl. The number one rule is to never read someone else's diary. But you've read so many.

Gristwood: Yes, I have, I know, but a lot of these women did in the end put their voices out there. And I did feel that sometimes they were stretching out a hand across the void. So I like to think that often they'd be happy to hear us listening with sympathy today.

Alston: Who knows? In the end, maybe I'll share mine too. You're listening to GBH's Morning Edition.

For her new book “Secret Voices: A Year of Women’s Diaries,” journalist and historian Sarah Gristwood spent time doing something that some people consider verboten: Reading other people’s private writings.

“A lot of these women did in the end put their voices out there,” she said. “And I did feel that sometimes they were stretching out a hand across the void. So I like to think that often they'd be happy to hear us listening with sympathy today.”

In hundreds of diary entries from women like Louisa May Alcott, Virginia Woolf, Oprah Winfrey and Anne Frank, she found an array of experiences and perspectives.

“I think the thing that most surprised me was how often the dilemmas that we think of as modern ones were echoed hundreds of years back,” Gistwood told GBH’s Morning Edition co-host Paris Alston. “Two hundred years ago and more, you get, for example, Elizabeth Fry, a Quaker great prison reformer, writing about how worried she was that her husband and her, I think it was 11 children, distracted her from what she thought of as her mission, her work. Well, juggling her career and family? That one hasn't exactly gone away today, has it?”

Some diarists did end up publishing their writings themselves. In other cases, family members or trustees held onto the journals after the women’s deaths.

“Some of these women, like Queen Victoria, must have known that there'd be public interest in her diaries. Other people might read them someday,” she said. “But even those women, I think, use their diaries to voice feelings that weren't acceptable in their own day: anger, ambition, frustration. A Bostonian, Caroline Healey Dall, writes about the fear of the coming childbirth. We can all understand that, heaven knows. But it wasn't the kind of thing you were supposed to say out loud.”

For some of the writers, keeping diaries with their feelings and thoughts a secret was a matter of survival: Anne Frank, for instance, was enduring horrific things as a Jewish teenager in hiding during the Holocaust, not knowing what her fate would be.

Women who are suffering various injustices and in conflicts around the world today may one day see their own reflections shape people’s understandings of the time we live in now, she said.

“That leads on to a very interesting question, which is whether the diary now is only the pen and paper or even the keyboard, or even whether you speak it onto tape, say,” Gristwood said. “I do wonder to what degree social media is a new form of diary, all the little happenings of every day. If you want to remember what you were doing, maybe voice some unpopular opinions, you turn to X, Instagram, whatever.”

Do we lose something when the diary goes public in that way?

“Maybe,” she said. “Or maybe we gain something as well. … But reading some of these extracts, I can't easily imagine anything I see on my social media feeds being quite that lovely.”