New England has a lot of unique, quirky customs: convenience stores we call “spas,” a “regular” at Dunkin ... and candlepin bowling.

If you mention the game to someone outside the region, you’ll probably be met with furrowed eyebrows or a blank stare. But “small ball” is classic New England. And a new exhibit at the Worcester Historical Museum, which runs through March, showcases candlepin bowling’s rise since it debuted at a Worcester billiards hall in 1880.

“History museums don’t always have to be Civil War, World War II kind of dusty stories,” said Vanessa Bumpus, an exhibit coordinator at the Worcester Historical Museum. “Candlepin’s an important part of our story.”

The exhibit features everything from old candlepin bowling balls and rulebooks to pictures of the game’s inventors and legendary figures it became popular among ... *cough cough* Babe Ruth.

One display shows why the game used to be called candlestick bowling. Before modern pins made out of plastic became common, the game involved inch-thick wooden dowels resembling candlesticks.

Robert Parrella is a local candlepin bowling ball manufacturer who partnered with the museum on the exhibit. He noted that the sport originated around the same time as several other types of bowling: duckpin , five-pin , and the traditional tenpin.

Candlepin was more challenging to play than the other forms because the smaller balls were harder to control and the narrower pins easier to miss. Still, the game took off because the lighter balls made it more accessible for people.

“Seniors, children, [anyone with] physical difficulties can play candlepin bowling,” Parrella said. “And it’s a lot of fun.”

By the mid-1900s, the game was popular across New England with recreational leagues in many communities. At candlepin’s peak around the 1960s, Parrella estimates there were 250 alleys across the region, with the majority in Massachusetts.

The game hasn’t expanded beyond New England, other than parts of Canada, because it’s more profitable for bowling supply manufacturers to produce equipment for tenpin bowling than candlepin. Parrella noted that tenpin alleys buy new pins every year, whereas candlepins last 15 to 20 years.

Bumpus also suspects that people outside New England aren’t enthused about how much harder candlepin is. Unlike tenpin, nobody’s ever hit 10 strikes in a row in candlepin, she said.

“And we’re New Englanders. We like a challenge. We’ll go on a boat to get lobster in the middle of a big storm,” she said.

Still, in recent decades, many alleys have closed because it’s expensive to find parts and difficult to keep up with maintenance. Rising real estate values have also put pressure on owners to sell their alleys to developers who convert them into housing or new commercial space.

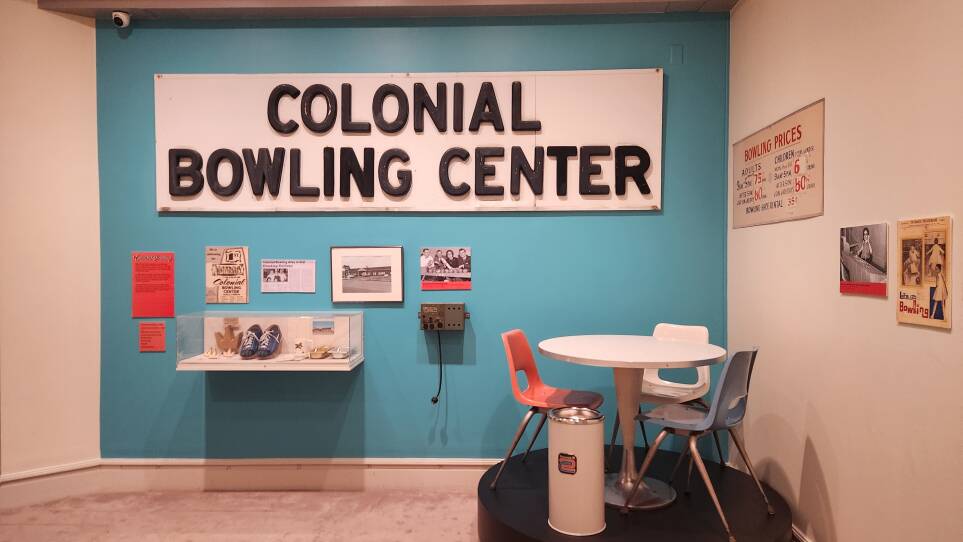

Parrella estimated there about 75 candlepin bowling centers left in New England. The last one in the sport’s hometown of Worcester — Colonial Bowling Center — closed in 2020.

That’s why Bumpus believes now is an especially good time for the exhibit at the Worcester Historical Museum. Maybe it’ll remind people how much they love candlepin bowling.

“It’s sad,” she said. “But we live in such a society now where things turn over so quick. There may be a resurgence in candlepin bowling in five years.”